Sometime back in 2008, the Hungarian film-maker Bela Tarr announced, somewhat surprisingly, that The Turin Horse would be his last film. This is perhaps fitting, as it would be hard to imagine where he might go next, were he to continue. The Turin Horse feels in some ways as if Tarr’s vision, unlike the world inhabited by its protagonists, has come to a satisfying conclusion.

Sometime back in 2008, the Hungarian film-maker Bela Tarr announced, somewhat surprisingly, that The Turin Horse would be his last film. This is perhaps fitting, as it would be hard to imagine where he might go next, were he to continue. The Turin Horse feels in some ways as if Tarr’s vision, unlike the world inhabited by its protagonists, has come to a satisfying conclusion.

Tarr’s inspiration for the film came from the story of an alleged incident in Turin in 1889, where the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche witnessed a horse being beaten by its owner. Nietzsche was so incensed at this scene of cruelty that he apparently flung his arms around the horse’s neck, in an attempt to protect it. Following this, he was said to have suffered a severe breakdown and eventually died a couple of years later. With this story in mind, and as a jumping off point for his last film, Tarr asks – what happened to that horse?

The Turin Horse is the story of a father and daughter living in a near-derelict farmhouse, in a remote rural landscape. The wind howls day and night; their daily meal consists of one boiled potato each, which they eat with their hands. There is no electricity or running water. We don’t know if this is a contemporary setting, or as the images might suggest, the middle ages.

This highly demanding film follows their daily routine, as they get up, dress, fetch water from the well and prepare the horse and cart for the daily journey into town. All of this unfolds in Tarr’s usual long, slow takes. Gradually, we see that the horse becomes unwell and is eventually too weak to move. Thus also begins the couples’ slow decline, as without the horse, their world shrinks; and so too does any hope of them being able to carry on. Added to this, there is a creeping sense of unease, as if an apocalyptic Judgement Day is about to reign over this wind-blasted Beckettian landscape.

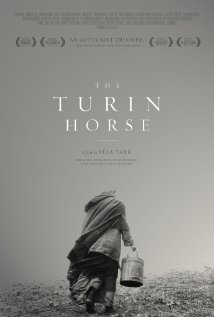

Tarr is once again aided by his cinematographer Fred Kelemen, whose gorgeous black and white images frame the hard-scrabble existence of the protagonists. Whatever you think of Tarr’s work, there’s no denying that there are quite beautiful images here – the close tracking shots of the daughter as she trudges to the well, carrying two heavy wooden buckets, her cloak and hair flying in all directions; or the close-ups of the father’s heavily lined face, looking like something hewn out of solid rock. Every shot is crafted and deliberate. Lighting is minimal, the interiors suffused with lamplight, closer to darkness than light. In contrast to the slowly deliberate action on-screen, Kelemen’s camera glides serenely in and around the characters in a wonderfully kinetic dance.

Marking this film as a truly collaborative effort, Tarr has again used his usual composer, Mig Vihaly, whose customarily melancholic strings infuse most of the scenes; and Tarr’s wife (and editor) Agnes Hranitzky also gets a co-director nod. Tarr has already spoken of his reasons for quitting film-making, and has outlined his future plans. However, there can be no doubting that European art-cinema will miss his singular imprint. It will be interesting to see if his influence extends to younger generations of film-makers, and if they will attempt to improve upon his good, if slow, work.

The Turin Horse is out now.

Watch the trailer